Cumha na Cuimhní: Loch Léin

Track 1 from a new record with Iarla Ó Lionáird, Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh, and Contemporaneous, introduced by an essay by Ó Lionáird

With this post, I am happy to begin sharing music from an upcoming album of collaborations with two remarkable Irish musicians, Iarla Ó Lionáird and Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh. The album will contain a set of three songs for Iarla and chamber orchestra—Cumha na Cuimhní—and five pieces for Caoimhín and chamber orchestra, both featuring the magnificent Contemporaneous (who commissioned the work—Midden Find—for Caoimhín). Much more about all of that in the coming posts; let’s dive in to “Loch Léin,” the first of the three songs from Cumha na Cuimhní, with Iarla as soloist.

Cumha na Cuimhní: Song #1, “Loch Léin”

- Iarla Ó Lionáird, vocalist

- Contemporaneous, conducted by David Bloom

- Traditional song

- Orchestral setting by Dan Trueman

The three songs of Cumha na Cuimhní are performed continuously as a complete set—a mini oratorio of sorts—and were premiered at the National Concert Hall in Dublin by Iarla and the RTÉ Concert Orchestra in September 2013. Read more about the original project in this article in the Irish Times, and a review of that concert, if you are interested.

I have asked Iarla to write about these songs so we can learn more about their origins and meaning. What follows is a fascinating essay about Martin Freeman and the Freeman Collection of songs from the early 20th-century, where Iarla first encountered “Loch Léin.” After the essay, I conclude with a few words about this particular setting of the song.

"Loch Léin" from A.M Freeman’s Ballyvourney Collection

I first encountered the song “Loch Léin” in a place where I heard many’s the song in my youth—the Top of Coom Pub or Barr an Chuma as we call it in my native language Irish. Technically the highest public house in Ireland, it sits just inside the Kerry Border on the road between Cuil Aodha and Kilgarvan. I witnessed many nights of song and music making there in my youth, listening and learning from some wonderful singers and musicians. Its location situates it on a linguistic faultline, if you will, since on either side of it are speakers of at least two languages—Irish and English—and this has given rise over centuries to a rich tapestry of song culture in both tongues and sometimes even in both simultaneously in the form of the Macaronic song. “Loch Léin” is a praise song which paints a picture of the area surrounding Killarney’s largest and most famous lake. The song’s structure deploys a commonly used trope whereby the poet compares this emplacement to all of the many places to which he has travelled along the length and breadth of Ireland, only to realise that Loch Léin stands incomparable to all else:

I travelled much and unceasingly in my youth

From the Shannon river to Charleville and

By the meadows Dingle yet saw no spot more

beautiful than the little white town by the top of Loch LéinI should not find it tedious, one day to be standing by the little tower of Céim

Looking on the fairest place under heaven,

Round by Doirín, Cathernane, And leafy Mucross

And Ross castle, where the heroes congregatedWhen November arrives it is like Christmas to them

They have brandy, honey and honeycomb

Fattened beef and fleshy badger

And Salmon from the Laune river leaping to the feast.I have walked by Dursey Island, Loch Erne and northward

By the Maine, and for a time in an army in Tuam

In all my long journeyings I have seen no place

More lovely then Loch Léin of the princely hosts.

and in Irish:

Do shiúilíos a lán gan spás i dtosach mo shaoil

Ón tSionainn go Ráth 's cois bánta Daingean an tSléibhe'

Ní fheacíos aon áit ba bhreátha 's ba dheise ná é

Ná’n baile beag bán ‘tá láimh le barra Loch LéinNíorbh fhada liom lá a bheith spás ar Thuairín an Chéim

Ag amharc ar an áit ba bhreátha is ba dheise faoin spéir

Mórthimpeall Thuairín Áth Charnáin is Mucros na gCraobh

Is ag Ros an Chaisleáin de gnáthach an ghasara thréanNuair a thagann an tSamhain, is geall le Nollaig ‘cu é

Bíonn acu gan amhras brannda mil agus céir

An mairt a bhíodh ramhar i dteannta an bhroc a bhíodh méith

An bradán ón Leamhan a fheabhas san don choire go léirÓ do shiúileas Buí Bhéara, cois Éirne, is as an thoir-thuaidh

Cois Mainge gan bhréag agus tréimhse in Arm-i-dTuaim

Ní fhacas in aon bhall den mhéid sin, cé gur fada mo chuaird

Ba bhreátha ná Loch Léin mar a mbíonn an máigh-shlua

What attracted me to this song in particular was its beguiling melody, which contains a certain melancholy, but also I was very taken with the use of imagery in the lyric and more particularly to the mention of the mythic heroes “Fianna Éireann,” who purportedly camped in the environs of the lake, testing and readying their battle skills in their ongoing mission as protectors of Ireland’s High Kings of old. There are two great mythological tracts in the Irish literary and folkloric tradition, the better known being that dealing with the exploits of the northern super warrior Cuchulainn, made infamous by W. B. Yeats and others early in the 20th century as part of the flowering of a new English literature in Ireland. But there is another, less well known set of stories and songs that concern the adventures of one Fionn MacCumhaill, mythic warrior and seer who captained the Fianna. Fionn, who when asked what made for the most beautiful of music, did not choose birdsong, the bell chime or the baying of the stag, but rather “the music of what happens,” an image of the nowness of the musical experience, later seized upon by Seamus Heaney in his poem “Song” with the lines:

There are the mud-flowers of dialect

And the immortelles of perfect pitch

And that moment when the bird sings very close

To the music of what happens.

—Seamus Heaney, ‘Song’

This corpus of stories and poetic lays has evolved through more that fifteen centuries and arrives into modern Irish late in the 19th-century in poetic stanzaic form known as ‘Na Laoithe Fiannuidheachta’ or the ‘Fenian Lays.’ What music there may have been for these poems is now lost to us, but what remains are these beautiful and mystical descriptions of the many exploits of this honor-bound band, as they do battle with monsters, with giants from abroad, with witches and tribal foes—all imbued with a strange and enchanting quality. ‘An Fhiannuideacht’ straddles two worlds, the mythic and the early Christian in the story of Irish civilization. It is this span that gives it its uniqueness, scale and power. Let us imagine these two worlds colliding, two cosmologies uniting and finding their way as one story that explains us to us. An Fhiannuideacht is such a story. It is at once rooted in the shamanic and richly totemic cosmology of ancient Ireland with its profound connection to the land, to the forces of nature and those unseen powers—the magic of that time—and then the tumultuous arrival on our shores of the Roman Christian world view, it too possessed of its own richly mystical cosmogony. Hyper vivid images of the Fianna suffused my thinking when I approached learning “Loch Léin,” but to find a good source for the words I would turn to a special repository and to the work of an extraordinary gentleman to whom I and whole generations of singers from my home region owe so much—Alan Martin Freeman—collector of what came to be known as The Ballyvourney Collection.

The very idea of a collection suggests to us a bounded, identifiable reality, an antidote to the flotsam and disorder of life’s entropic processes. We seek to order our world in all that we do, from the stone walled fields of the west to the classificatory mathematics and language that organizes whatever knowledge we have amassed in the thousands of years of human civilization. Libraries, those once proud bastions of accrued wisdom, may have given way to the light speed world of data sets which we now inhabit and interrogate, but, even so, as the methods of transferring information from one location to another may have become passé and its organization somehow now graduated from the immediate physical realm to something more ephemeral, underneath the gleam of touch screens and silent distant server farms, we still live in an organized and collected world. In fact, though the methodology of access and indeed interaction has evolved, our existence today is arguably more than ever dependent on the collection, the gathered, the classified and understood. And our culture depends on these permeable yet bounded containers of knowledge to function in an ordered, predictable fashion. The collection is a representation also of identities, perhaps idealized but still potently able to transmit an idea or ideas that define, explain, illuminate our understanding of ourselves and our world.

One hundred and nine years ago a certain Alexander Martin Freeman visited the parish of Ballyvourney in County Cork with his wife Aida on a holiday. A graduate of Lincoln College, Oxford and a native of Tooting in the metropolitan London area, he had become, through his association with his wife, a native of Donegal, quite acquainted with and interested in Irish culture and folklore and the activities that occurred in Irish circles in London in the early part of the century. He was a regular attendee of the then Irish Literary Society in Hanover Square and in time acquired a good knowledge of the Irish language having studied under Kuno Meyer. The trip to Ballyvourney must have had a great impact on the Freeman, as on the following year they returned for a visit lasting some three months, during which time Freeman spent weeks filling his notebooks with song tunes and words from a handful of singers. These songs would in all likelihood have seen light of day earlier were it not for the onset of the First World War, which saw Freeman enlist in the Royal Army Service Corps and being posted to Salonika. On his return from war the detailed editorial work so evident in the collection resumed and what has become known as the great Ballyvourney Collection appeared in the Journal of the Folk- Song Society 1920–21 as numbers 23–25. To quote the great Irish Folk song collector Donal O’ Sullivan writing in the Journal of the Folk Dance and Song Society in 1960 following on the occasion of Freeman’s death in 1959, he says of the collection:

It consists of nearly a hundred songs, with the original texts, prose translations and annotations, constituting incomparably the finest collection published in our time of Irish songs noted from oral tradition.

It seems important to explain that none of this would have been possible were it not for the efforts and enthusiasms of the Folk Song Society which was established in London in 1898 and whose membership boasted such luminaries as Bela Bartok, Vaughan Williams, Cecil Sharpe, Edward Elgar and Sir Charles Villiers Stanford. Aside from these, however, perhaps its most important and influential member was one Miss Lucy Broadwood, herself a noted collector active both in Ireland and in Britain. She would go on to become the Society’s president and, aside from being arguably its finest scholar, applied her skills along with Robin Flower in assisting with the complex task of editing, annotating and preparing for publishing the various collections, including Freeman’s Ballyvourney Opus. In an article written by Society member Frederick Keel in 1948 outlining the history of the society, we are told:

For it must be remembered that the Folk Song Society were amateurs in the strict sense of the word. They could only learn their chosen work by doing it and there were few among them so experienced in it that they could ‘teach’ to others something that cannot be academically taught.

Collectors went out to the English Countryside, to the Manx lands, to Ireland and elsewhere armed only with a leaflet which the Society’s Committee of Management had provided entitled “Hints to the Collectors of Folk Music,” which Keel remarks “laid down unexceptionable principles of collecting which later experience found no need to alter.”

Thus armed, the various collectors could carry out the Society’s aims in the field, aims fueled by a vision of the folkloric as propounded here by Society Vice President Sir Hubert Parry on the occasion of the first General meeting of the Society on February 2nd 1899 as being “among the purest products of the human mind,” something that “grew in the heart of people before they devoted themselves so assiduously to the making of quick returns,” growing there “because it pleased them to make it, because what they made pleased them; and that is the only way good music is ever made.” And, he continued, “it is a hopeful sign that a society like ours should be founded to save something primitive and genuine from extinction…”

Scholars of a then nascent discipline of Anthropology might have had cause to question in later decades some of these sentiments but what cannot easily be critiqued is the genuine desire of the society to find and thereby preserve that which they perceived as being in the maw of imminent and final loss, for future generations.

The task of collecting songs from a small group of native speakers in a foreign land requires considerable skill and determination and it is acknowledged that in his efforts Martin Freeman had considerable support from his wife Aida. One unnamed correspondent quoted by the society in an obituary to Mrs. Freeman states that:

When I first met her shortly before the Great War, Mrs. Martin Freeman was a prominent figure in Irish literary society in Hanover Square where she took part in amateur performances of Irish plays and played folk airs on the violin at concerts. Her visits with her husband to Ballyvourney in 1914, where her tact and knowledge of Irish country folk and general helpfulness in smoothing difficulties made it possible for him to carry out his work, resulted in that incomparable collection of songs published in volume VI of the Folksong Society Journal, the greatest Irish collection of modern times.

Freeman himself must also have been possessed of the type of personality that allowed him to gain people’s trust sufficient for them to sit with him for days on end and recall song and story. Apart from the great store of songs that this collection contains, Freeman’s own recollections and notes regarding his encounters with his chief informants are both revealing and profound. For instance in page XIX of Volume 6 number 23, he describes for us the four key singers on whom he relied for much of the collection. Of Peg O Donoghue he says the following:

About 78 in 1914. Illiterate. Has lived laterally in the English-speaking end of the parish. The best natural musician I met in the district. She can hum a tune without the words, and sing through a long verse in short sections, pausing, and even repeating sections, and scarcely ever alters the pitch in the process. She is infirm, emotional, excitable, and I seldom can get down more than one short song from her at a sitting. When singing a complete song she becomes ecstatic.

I have always been struck by Freeman’s last phrase here and have tried to imagine what he may have witnessed as this elderly and clearly beautiful singer achieved a change of state during her performance of the song. In a world now which leaves less and less to chance and less space for the imagined, what Freeman does not tell us beyond that word “ecstatic” leaves us with a sense that in fact the experience was an unforgettable one, one which would have to be experienced first-hand and could not easily be conveyed by the writer’s hand. It suggests a liminal area best left to the moment and to the silent, personal recollection. I have carried that image of the singer achieving a special grace through the act of song with me down through the years as a strange, inexplicable, talismanic metaphor for what might be possible in our music, what might be achievable in the performance of these musical objects, radiant of an intangible and beguiling beauty.

Freeman engaged with three other key informants during his time in Ballyvourney: Miss Abbey Barrett (who provided the song “Loch Léin”) who was 37 in 1914; a Mrs. Mary Sweeney who was also 78; and a Mr. Conny Cochlan of whom he says:

Labourer. Said to be over 80 in 1914, but no one knows his age. As active and alert as a man of 40; a most interesting talk; does not read or write; speaks both Irish and English well; passionately fond of Irish; a tuneful and easy singer, never forcing a note. He gave me about half the songs in this collection and has forgotten a large number of others. Some of these were given me by other singers, and when I read them over to him he often supplied variants for additional words, generally improvements of the sense of sound. These contributions were of course not critical alterations, but memories. He does not dissociate words and tune and thinks that if you know enough Irish you should be able to “put a voice” on any poem. NB. In Ballyvourney there is no word for “to sing.” “Say a song,” is the expression used and if you want a poem spoken instead of sung you must ask the person who knows it to “say it in its words” and not to put any voice on it.

But beyond the fact that it was Conchubhar Ó Cochláin, this elderly man from the town land of Doire na Sagart, who supplied Freeman with much of his trove, it is clear that he also had a catalytic effect on the overall process of the collection’s progress and development. It is clear also that his interactions with Conny Cochlan illuminated in large measure the anthropological, linguistic and social history of the region as Freeman alludes to here dealing with songs in the English language:

“I never had many English songs,” said Mr. Cochlan. “For I was at work too early, and I never had time for any ballets,” (as he calls them) “and I left school too early.” This was spoken with no change of regret and rightly so; for it would be difficult to find an old man happier, healthier, more active in mind and body than my chief contributor. In any case it is highly probable that if had had more “ballets” and English and so-called education in boyhood he would not have possessed, in old age, those accomplishments which made his help so valuable in compiling this book of songs.

I feel bound in gratitude to say a little here about his share of the work; but as I drew my knowledge of the neighbourhood, its people and traditions and local speech, primarily from him, merely supplementing it from others, adequate acknowledgement is impossible. When I had taken down a little more than half of those songs of his printed above, he announced that he had no more; and I began to visit other singers. But I still went to see him every morning, to obtain information which might throw light on the various material I was collecting; and it must have been at the beginning of this stage in our relations that people began to talk about us, and to make jocular enquiries as to how the work was going on. They thought it quite natural (apparently) that I should wish to get songs from a noted singer; but that I should go daily to his house to study struck them as eccentric. One morning immediately after I entered his kitchen he said, “Do you know that I went into the village yesterday? And before I got there, just as I was passing the gate of the man with two cows, a man met me and he said, Conny, is it not the most remarkable thing that a man should come here from England and go to school with you? He did, on my honour!”

This and similar incidents impressed him a good deal and whereas before he had been hospitable and obliging but somewhat bored with my attention to detail, he now had a godfatherly interest in the work; and we collaborated as truly as ever any two men. I read over to him every copy of words which I took down from other singers; and he always had plenty of remarks to make about them, especially if they were noted from young people. But whatever their source might be, it generally happened that he had at one time known or partly known the songs, and my reading would at once prompt his memory, which, though he fancied it dead, was only dormant. His natural accuracy and familiarity with the poetical language gave great value to his textual variants. I only recorded as a rule those of his variants which were memories not suggestions. But his ear distinguishes defective rhythm or assonance at once and I had several proofs that his knowledge and understanding are wide enough to make a good judge, according to the accepted standards of an 18th-century poem previously unknown to him.”

There is evidence in Freeman’s writing that a real trust and friendship developed between the two men in their shared endeavour. In the end we glean from the author’s favourite contributor valuable personal insights into the local culture, language and the changes which the new century would inevitably wrought upon their way of life and upon their music.

In his last section of the journal dealing with Mr. Cochlan, Freeman shows us that the local people possessed a keen awareness of the precipitous vista that lay ahead for their way of life and their deep desire to somehow forestall the corrosive erasure that time would surely bring to bear:

He was most interested in the collection of songs and more than once advised me to put them into the press and make a book of them for fear they should be lost. (At the time I hardly suspected any more than he that the folksong Society would enable me to do this.) When my last days in the country arrived he talked with great pleasure on the amount I have recovered. He delighted in the fact that I had filled seven books with music and five with words, and declared that we had done a great work. “There are not,” he said “any two men in Ireland who could do what you and I have done this August to October. For even if you found a man who knew as many songs as I know, his voice would break if you sang so much. And for you to be able to write down the words and the voice exactly as we sing them—and you were not brought up in Irish! Friends meeting among the road would say: “Conny, you will never remember all those songs again. What do I care,” he would answer, “so long as this man has them written down in his book?” The people I was living with and their numerous circle manifested a lively interest in my quest and at my industry and were astonished at the result. But they told me that I had a mere remnant of the songs of the neighbourhood. “For the Irish is gone, and the old people are gone, and the songs are gone. If you had come here 20 years ago, then you would have got some songs!”

This collection is by any measure an extraordinarily rich hoard of song and poetry and apart from the fact that it contains an invaluable core sample as it were of our singing culture more than 100 years ago, the method of its collection, without the means of sound reproduction such as was available at that time, confers upon the work an oddly literary and poetic focus. It also paradoxically, considering the methodology deployed in the transcriptive of process (which to my mind displays extraordinary scholarship and dedication), supplies us with unusual insight into the sonic and timbral character of the Irish language in its common usage at that time. The entire collection is notated using what Freeman calls “The Simplified Spelling of Irish,” developed chiefly by the Gaelic scholar Dr. Osborn Bergin in 1907, as an aid to the learning of Irish. The system is phonetic in nature and Freeman states that its deployment arose from his belief that, as he puts it:

The literary spelling of Irish is unsuitable for the recording of folksongs but on account of the complication and inadequacy of the system itself and because of the numerous and wide divergences in spoken Irish… Thus however much and however well you may have studied the language a collection of folk songs if given in the literary spelling would not tell you its message with any approach to complete this if you do not happen to know the district in which they were collected.

He illustrates his point with the Irish word Amhrán for song as having many variants including:

Aurán, abhrán, úrán avarán, and óran.

Using the approaches propounded by Freeman, what eventuates is a collection which can be sounded according to the pronunciation guide included in its chapters, and when deployed with the translations gives us a very accurate and full, sounded picture of speech patterns in that area a century ago. And in my own studies I have found this to have been a key attribute of the collection which gives it tremendous range and aesthetic depth. Freeman concludes on his notes regarding pronunciation:

We are not concerned with the encouragement of Irish learning or the education of Irish Speakers. But the new system is of great value to collectors and students of folk songs, because it provides a means of showing:

(a) Approximately how the syllables are apportioned to the musical notes, and

(b) Exactly how each syllable was pronounced by the singer.

And to know how something is sounded in relation to the music is an invaluable guide in the process of recovering, remaking in sound and re-living the songs contained within the collection’s covers. Reading through the collection I find myself keenly aware of the sound itself, embedded in the phonetic structure as it is through Freeman’s fastidious notation, and I am reminded of the breath and grandeur of the spoken language of our forebears and of the syncretic poetic awareness that is alive in the everyday language of these people and what might now seem as their extraordinary engagement with the poetic experience as a normal pattern of their daily existence.

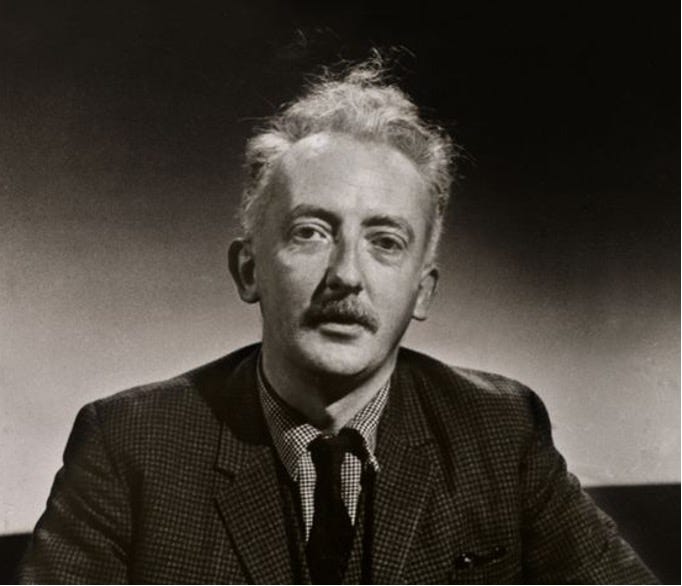

Recently an extraordinary document has come to light—a recording of A.M. Freeman himself singing a selection of songs from Ballyvourney on the Scottish Island of Canna for his friend John Lorne Campbell in 1951. Here I include his palpably learned version of the song ‘Ar Mo Thaisteal Trí Bhaile Bhúirne / As I Roamed Through Ballyvourney. It is a vivid and telling record of his fidelity and fealty to the songs of the people of that region and of his own keen ear and mastery of their rich song culture:

A.M. Freeman singing ‘Ar Mo Thaisteal Trí Bhaile Bhúirne / As I Roamed Through Ballyvourney

And how was it, one may ask, that I came upon this collection and the many treasured songs it contains, including “Loch Lein?” That is due in large measure to the arrival in the village of my upbringing—Cúil Aodha—a notable and mercurial figure who towers over the manifest development of Irish Traditional Music in Ireland in the 20th Century: composer Seán Ó Riada.

The arrival Of Sean O’Riada to this remote corner of Ireland in the 60’s was opportune. In Cuil Aodha at the time he found a society under considerable economic stress with no local industry to speak of and a population whose younger generation, though brought up in an environment of traditional values (which included a latent religiosity and arguably a linguistic and cultural insularity), were beginning to see and move outside it. It was a society to those within it whose cohesion was fraying at the edges under pressure from forces much more powerful than it could on its own muster. Many of the younger singers were toying with the show-band phenomenon and habitual speaking of Irish was on a steady decline. O’Riada’s arrival heralded what I would advance as a deliberate re-activation of the local music culture. This involved an intensive trawl of old collections and in particular The Freeman Collection, the tape-recording of old singers, the learning and adaptation of archive material and then the exposure and celebration of these renascent musical artefacts in public performance not only in the church but also in halls throughout the country.

Cuil Aodha would come to be seen as the last step in O’Riada’s cyclic development as an artist, a journey that brought him from a familial traditional music background through the explorations in serialism of his Nomoi compositions and back again, transformed by the spectacular success of his film music settings for Mise Eire and Saoirse to that of a public figure experimenting with and extolling the virtues of a native, ancient and noble music culture and language as he saw it. For some, particularly those who justifiably looked to O’Riada as the last hope for the development of an Irish art music, this atavistic migration would come to be interpreted as a catastrophic failure and betrayal of his true gifts. For the formerly solo singers of Cuil Aodha, mostly drawn from small farming backgrounds, his philosophical and musical about turn would be a cultural and economic renaissance. O’Riada’s reputation and panache in time secured new industries for the region, and gave its music culture a platform and confidence it had never before experienced. This confidence also fed off the other sources, most notably the re-emerging nationalism of the northern troubles and a latent re-inscribed sense of nationhood as prescribed by Douglas Hyde and the Gaelic League. These were not difficult energies to harness since the regions surrounding Cuil Aodha had half a century earlier been hot beds of guerrilla insurrection prior to the establishment of the Irish Free State. A cultural re-enactment of the sort promulgated by O’Riada found easy reception in the fertile ground of a place which Republican ideologue and martyr Padraig Pearse had called ‘the capital of the Gaeltacht’ in a 1908 article in the ‘Claidheamh Soluis’ (Referring to the parish of Ballyvourney).

After Sean O’Riada’s untimely death in 1971, the choir continued under the direction of his then 17-year-old son Peadar and continues to this day. I have often pondered upon O’Riada’s reaction when first he read the songs in the Freeman Collection on the dusty shelves of the library at University College Cork. When that may have happened is not clear but local sources have indicated that upon his arrival to Cúil Aodha he had already scrutinized its contents and had also developed a strong liking for some of its songs in particular. Peg O’Donoghue’s rendition of the beautiful Aisling Gheal would become O’Riada’s party piece on the piano or harpsichord. It would also be one of the songs first learned from the collection by famed sean nós singer Diarmuid Maidhcí Ó Súilleabháin and eventually by myself. Other songs from the collection also permeated the repertoire of the choir when performing concerts, or Claisceadail as they were known, around the country. Songs such as “Bímís Ag Ól,” “Tuirimh Mhic Fhinín Dhuibh,” “An Habit Shirt” and “Éistigh Liumsa Sealad” became embedded in the corpus of songs that would be performed regularly. Other individual singers subsequently explored the text and found songs that were sometimes familiar to them and at other times newly uncovered gems that had long lain silent awaiting re-discovery.

For me the Freeman Collection remains a landscape of almost infinite possibility—a truly dynamic and rich resource from which to draw, learn and grow. It is a particular delight to be able to re-present songs such as “Loch Léin” from Freeman’s work in a radical new way through Dan Trueman’s unique vision, but also in a manner which at its heart remains, I believe, very true to Abbey Barret’s rendition all those many years ago.

—Iarla Ó Lionáird, April 2024

Dan here again!

My approach to “Loch Léin” and all three of the songs in Cumha na Cuimhní was to endeavor to inhabit each song as deeply as possible and not force the song and Iarla’s performance into boxes that were easy to notate and obvious for an orchestra to play, but at odds with the song itself. To “say a song” the way Iarla does means the “music” and the “words” are so intertwined as to be inseparable, the rhythm and phrasing of the text and music one and the same, which does not always fit nicely into simple time signatures:

Fortunately, David Bloom, conductor of Contemporaneous, is terrific at handling this delicate dance between Iarla and the ensemble!

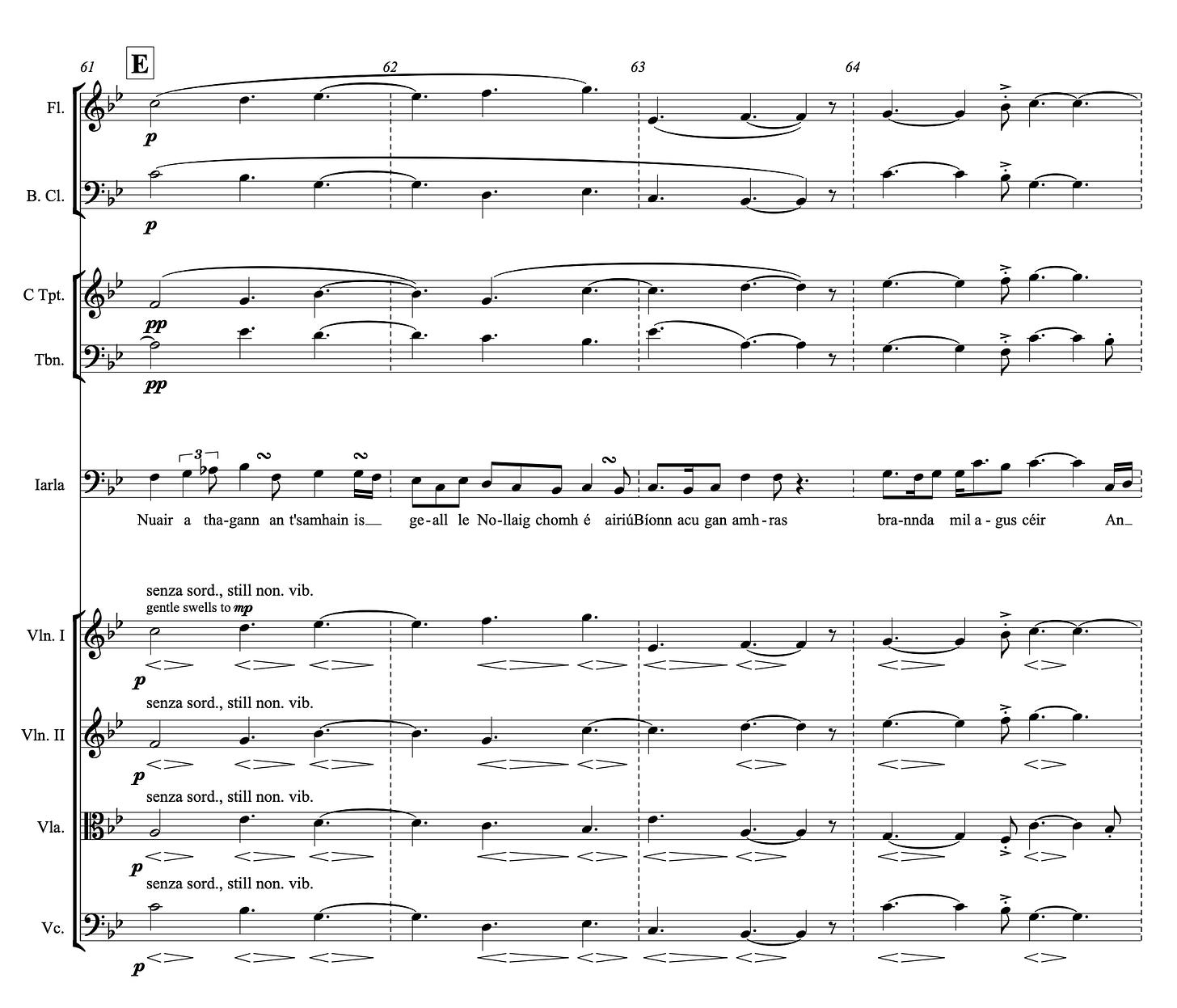

For my setting of “Loch Léin,” we hear each stanza preceded by a kind of pre-memory of the stanza, a foggy frame that might represent our efforts to conjure the song from our memory, to fish it out from the depths of our internal lake of neurons (perhaps like Conny Cochlan, when he was remembering songs he had “forgotten”), after which Iarla arrives to bring the memory to life. Here’s what the “fishing” looks like before the third verse:

and then the beginning of the third verse after it has been “caught”:

I will say more about this process with the other songs, but I’ll leave it for now, and am delighted to be launching this particular series of posts about an album that I can’t wait to release!

Thank you for the article. I enjoyed your work with Iarla, Paul Muldoon and Eighth Blackbird on Olagon. Very much looking forward to hearing this new work and hope perhaps there will be a live performance.