Inside Out

Prelude #1 for bitKlavier

Some years ago I set out to compose 24 preludes for bitKlavier, two in each key signature, the idea being that the key signatures would encourage me to think about the hands in different ways on the keyboard. I’ve composed 12 so far, and am excited to share them over the coming months. Cristina Altamura and Adam Sliwinski have been inspirational partners in this process, and have made beautiful recordings of all 12, sometimes with different approaches and interpretations.

After sharing these 12 here, we will release them as an album, both digitally and on vinyl. The cover art for the project will be based on a painting by my mother, Judy Trueman, which I think captures some of the essence of the project.

Many of the pieces take as inspiration an existing piece, perhaps in a general sense, but sometimes in a much more specific way, not so unlike Bach’s Garden above.

The first prelude, however, takes the piano itself as primary inspiration, turning it inside out and then back again over the course of the piece. bitKlavier is a sample-based instrument, meaning it is based on using many small recordings of each note of the piano. Over the years, sample library creators have learned that there is more to these instruments than just the notes themselves; the mechanics of the instruments contribute to their feel and sound in crucial ways—when the hammers that strike the strings inside the piano fall back into place, they make a quiet clunk, and when the dampers silence a string when a key is released, the string actually rings on a bit, giving the instrument a quiet, short afterglow; even the sustain pedal makes a satisfying quiet thunk when released. Without these subtle components, the sound of a sampled instrument often seems sterile and lifeless, so some sample libraries include them after painstakingly recording and editing them (including the bitKlavier Grand sample library). Inside Out begins with just the sounds of the hammers, foregrounded so they sound almost like drums. The afterglow samples join after a bit, followed by some bitKlavier specials (the nostalgic and synchronic preparations, creating little reverse notes and pulsed patterns), and only well into the piece do we hear the “normal” pitched sounds of the piano, which then gradually disappear, leaving us with just the sounds of the piano innards again. Check it out:

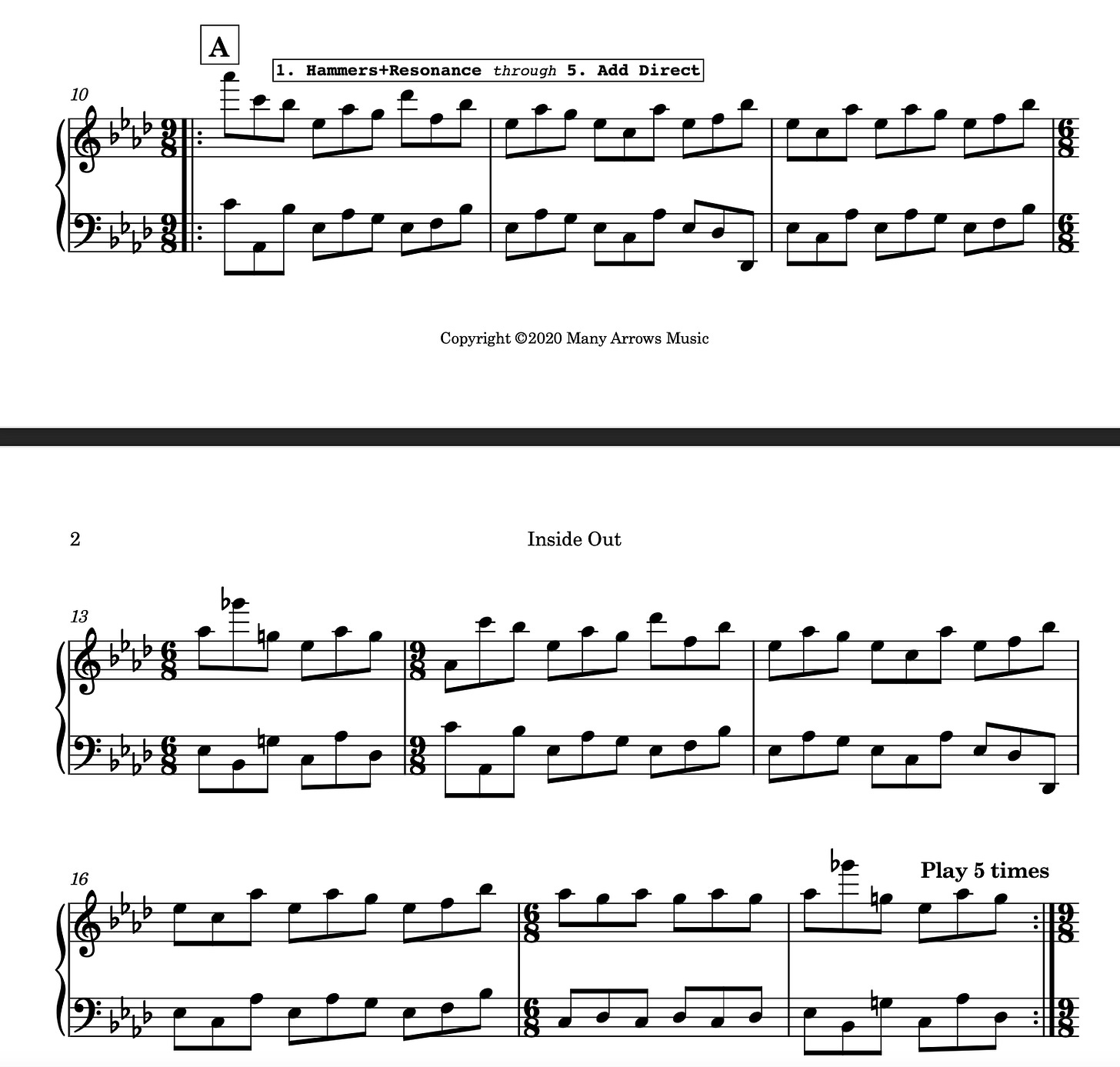

It’s basically one riff, repeated over and over, and the first note of the pattern causes a new component of the piano to be revealed (or removed, in the latter half of the piece). Here’s letter A, where the riff is repeated five times, each time introducing a new component of the instrument:

I asked Cristina for her thoughts about playing this piece:

Inside Out stretches your musicianship and delights in surprising ways, by both inviting you to grapple with unusual digital effects and reaching back into the past.

The piece requires traditional piano playing skill to execute. However, selected keys of the melody also act as computer buttons—trigger notes—that send commands to the program to produce effects (read about them here) that the composer programs in advance, but which behave in real-time. The functions are elegantly hidden so that the performer simply plays the notes on the score: the rest is done by the bitKlavier program. Also… they may or may not play the sounds you expect them to, though they behave consistently, without any programmed randomness.

I started learning Inside Out on an acoustic piano because Dan told me that the main nine bar cycle was inspired by a Chopin prelude. I soon realized that with these preludes he wanted to draw more connections between received piano practice and this new instrument (his first bitKlavier etudes were written for Adam Sliwinski—best known as a percussionist—and had leaned heavily on dizzying rhythmic play). The technical challenges in this piece mirror some of those encountered in Chopin’s prelude in E-flat Major—patterns which include large intervallic jumps on black keys, all while maintaining a brisk corrente tempo of triplets. Additionally, Trueman doubles the melody two octaves apart in parallel and contrary motion of the hands.

This melody repeats over and over throughout the whole piece, with only a brief bridge-like middle section of ever larger intervallic jumps—always perpetual motion triplets.

Each repetition introduces different articulations and sound components one at a time. For the first half of the piece, with each repetition, the effects are layered onto the previous one, compounding the sounds to achieve a concertato (the sense of a group of instruments playing at once). I began to call it “composite listening,” where singing the base melody internally is crucial to maintaining the supple muscle memory, while an outer awareness keeps track of the layers of surface effects. The second half is a process of subtracting these effects one by one until I’m playing phantom notes producing only the sound of hammers.

In Chopin performance practice, especially in the Nocturnes, one encounters the repetition of the same melody as an expressive device. The most nuanced Chopin performances are those that inflect so effectively that the listener hears melodies in a new light with each repetition. Chopin adds tiny, imperceptible changes, often adding or omitting one note of the melody to signal nuanced mood shifts. He’ll add delicate ornamentation to a specific note to stress it much like an actor might practice stressing a different word of the same sentence so that each repetition carries a new meaning.

I was charmed that Dan jumped off of Chopin to introduce his own ideas and the bitKlavier’s vast vocabulary of possibilities. It signaled an invitation to adventurous pianists to come out, play, and explore this open-source invention. It also seems a fitting homage to the revolutionary nature of Chopin’s keyboard writing.

I was indeed thinking about some of Chopin’s Preludes while writing this one. In fact, most of these bitKlavier preludes take as their starting point an existing piece of music, and I often focused on the physicality—how the hands navigate the keyboard, and how the body as a whole is engaged—that these existing pieces induced more than their specific pitches and rhythms. I think the connection to the Chopin prelude that Cristina references should be clear:

To be honest, I can’t remember how I got from the Chopin to Inside Out—I often can’t remember what happened after a composition session a day later!—but the notion of engaging the hands in this repetitive though expressive sort of athleticism was at the fore of my thinking. The kinds of athletic challenges that Inside Out poses vary significantly over the course of the piece; for instance, at the beginning, when only the sounds of the hammers falling back into place are present, the pianist hears nothing when they press the key down—the “phantom notes” that Cristina refers to—and gets the sound of the hammer when the key is released! It’s totally counterintuitive, and keeping this pattern steady and convincing is then quite a challenge, both at the beginning when the attacks are silent and then later maintaining that steadiness as the sounds of the attacks emerge. Naturally, this is totally different sort of challenge than any presented by the Chopin.

Here is the score for Inside Out, and the bitKlavier galleries, if you’d like to try it (of course, you’ll need bitKlavier as well!):

And finally, the audio recording of Inside Out, as it will appear on the album when it is released, performed once again by Cristina Altamura: