Project Resonance

The Hardanger Quartet, and the first ever Hardanger d'Amore Cello

Project Resonance began with a gift: in the summer of 2024, Lynn Berg donated a beautiful matched quartet of Hardanger instruments—including among the only Hardanger cellos and violas in the world—to me and the Music Department at Princeton:

I promptly put them into the hands of the intrepid Bergamot Quartet, whom I had been working with on a set of quartets, quintets, and sextets, for strings in scordatura (I wrote about THAT album, which is for conventional stringed instruments, NOT Hardanger instruments, here). They took to them like fish to water (or milk to tea?):

Before I write more, we might as well listen; here are three traditional Norwegian tunes that I arranged for the quartet that we are releasing today:

The Hardanger fiddle is the national instrument of Norway, and has been around for centuries, as long as the violin itself. It is played primarily for dance, though also for weddings and for intimate concerts. It is typically played solo, and the traditional tunes are complex, with modular, flexible forms. Here’s Hauk Buen, who made my own instrument and was one of the giants of the tradition, playing for dancing:

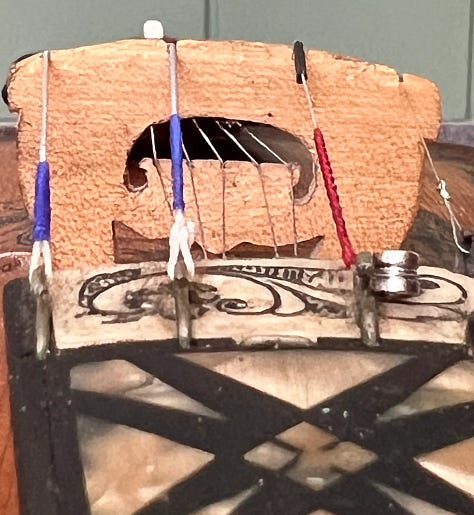

Physically, the instrument is quite different from the violin and fiddle, featuring a set of sympathetic strings that run under the fingerboard and sing along as you play, and a flat bridge that encourages double-stops:

The main strings are typically tuned up higher than the violin, in different intervals to one another, and the string/body length is a slightly smaller than the violin. Here’s the normal violin tuning (GDAE):

and a typical Hardanger tuning (BEBF#):

and here are how the sympathetic string—or “understrings”—are often tuned (C#EF#G#B):

One characteristic of the Hardanger fiddle is that it can be tuned up in many different ways—scordatura, or cross-tuning—and much of the music (traditional and contemporary) emerges from that flexibility; what you hear above is just the most common of the tunings.

Broadly speaking, the Hardanger fiddle is under less tension than the Classical violin, and is optimized to create an immersive, localized resonant space (think: a fiddler in a small or medium sized chamber or dance hall, trying to create a warm, immersive soundworld), rather than for volume and projection (think: a soloist in front of an orchestra trying to be heard at the back of a large concert hall).

Traditionally, the Hardanger fiddle is a solo instrument, which offers freedom to the fiddler to play tunes in various ways, and historically it has not had larger siblings like the viola or cello… and not really been a chamber-music instrument… until very recently!

Lynn’s gift of the Hardanger Quartet offers us a novel opportunity—a laboratory of sorts—to explore a whole range of musical possibilities with this expanded instrument set, especially when in the hands of Bergamot Quartet; their remarkable combination of intense commitment to contemporary chamber music (I’ll never forget their multiple performances of Lachenmann’s Grido that I’ve been fortunate to experience up close) and deep interest in non-classical “fiddle” music (not to mention their extraordinary musicianship and chamber music acumen) puts them in a unique position to break new ground with this laboratory; I am thrilled to be a co-conspirator in this part-chamber-music, part-composition, part-traditional-music, part-just-damn-fun project! Today we release the first six videos of work we’ve done together; I’ll write more about these in coming weeks…

But, there is more to say today!

My own work with the Hardanger fiddle has not been confined to the design of the traditional instrument. In 2010, I commissioned a new kind of instrument, now called the Hardanger d’Amore, which is a hybrid of the Hardanger fiddle and the 5-string American-style fiddle used primarily in Old Time/Appalachian music; my inspiration for the instrument came from my collaborations around that time with Old Time fiddler Brittany Haas and her remarkable 5-string playing—I wrote about this recently here.

Tuned lower than the Hardanger fiddle, to a similar pitch as fiddles from America and Ireland, and featuring a 5th lower string, the Hardanger d’Amore is a deeper, warmer instrument (the traditional Hardanger fiddle is characterized by its bright, shimmering, high frequency timbre), still with the affecting resonance of the sympathetic strings and overall design to maximize resonance rather than projection, along with a similar tuning flexibility as the Hardanger fiddle (we play the d’Amore in many different tunings!). The maker of the Hardanger d’Amore, Salve Håkedal (one of Norway’s preeminent instrument builders), has since made over 50 of these instruments, for players around the world (Caoimhín Ó Raghallaigh being perhaps the most well known), and has a 7-year waitlist; multiple other makers have now taken on the instrument to meet the demand. The Hardanger d’Amore has been central to my own musical explorations since, enriching the world of resonance-focused instruments and offering an expressive space that invites quiet, detailed playing, and pure tuning (so-called just-intonation, where tuning is based on the overtone series, in part to maximize resonance).

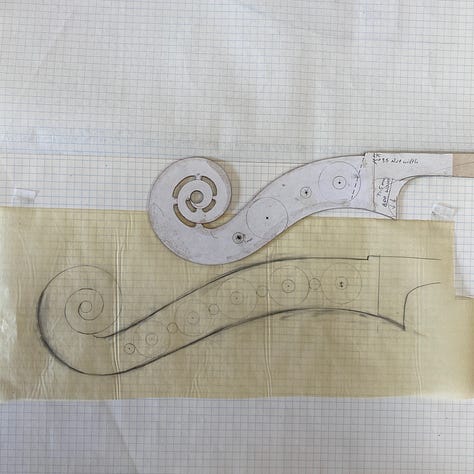

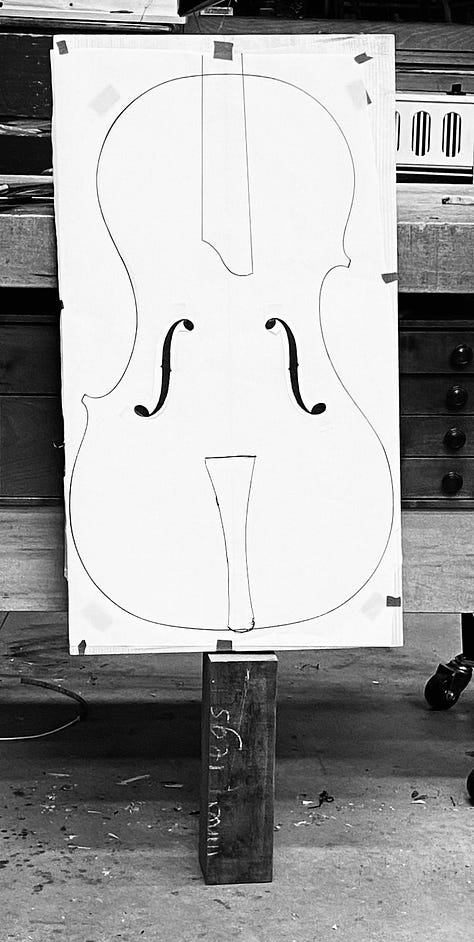

The expansion of the Hardanger fiddle to the Hardanger quartet begs another question: what about a Hardanger d’Amore quartet? Given that the Hardanger d’Amore already has 5 strings, venturing down into the viola range, this really means: what about a Hardanger d’Amore cello? Today, we are so excited to share that David Finck, a maker of cellos and violins and one of the new makers of the Hardanger d’Amore, has begun work on the first ever Hardanger d’Amore Cello:

Tuned an octave below the Hardanger d’Amore (so, with a 5th string above the usual top string of the cello) and with a full set of sympathetic strings, the instrument will, like the Hardanger fiddle and the Hardanger d’Amore, allow for a range of different tunings (some examples, from the bottom string up: DADF#E, CAEAC, AAEAC#, BbFCAE, and more). Or so we hope! It’s all a bit of an experiment!

This cello, together with two Hardanger d’Amore by Håkedal and a Hardanger d’Amore already made by David (with Salve’s generous guidance), will make up the first ever Hardanger d’Amore Quartet—I love how this quartet will reflect the hybrid Norwegian/American identity of the Hardanger d’Amore, with two instruments by Salve and two by David. And the two quartets together—the first ever matched Hardanger Quartet, and the first ever Hardanger d’Amore Quartet—will be an unprecedented laboratory to explore stringed instrument design, performance practices, and compositional possibilities. I am so excited! I am already imagining music for the d’Amore quartet, and for the instruments of the quartet mixed and matched in various ways (Caoimhín and I have combined the Hardanger fiddle and Hardanger d’Amore in various ways for some time now; see this, for instance), and I’m also keen to hear what other composers do with these instruments (this fall, I will be leading a graduate seminar at Princeton with our fabulous composers and Bergamot to explore just that!)

I want to thank Lynn for his incredibly inspirational gift, and Loretta Kelley for facilitating the gift. I also want to thank Salve for making such a wonderful new instrument in the d’Amore and being so generous with other makers like David, and David for being so thoughtful and adventurous in taking on the challenge of a Hardanger d’Amore Cello. And I want to thank Bergamot for their partnership in this delightful crime of sympathetic resonance! Skøl! Sláinte! Tully all around! Cheers!