The Seventeenth Hotel: Giants Begone

track four from a new album of songs

Giants Begone

by Dan Trueman, track 4

from the album The Seventeenth Hotel, with

- Molly Trueman (voice)

- Jason Treuting (drums)

- Florent Ghys (bass)

- Dan Trueman (bitKlavier, Hardanger d’Amore, voice, whistles)

- Recorded by Molly Trueman, Dan Trueman, and Matt Poirier

- Mixed by Matt Poirier and Dan Trueman, Mastered by Matt Poirier.

- Artwork by Judy Trueman

read on, if you are so inclined, or just listen…

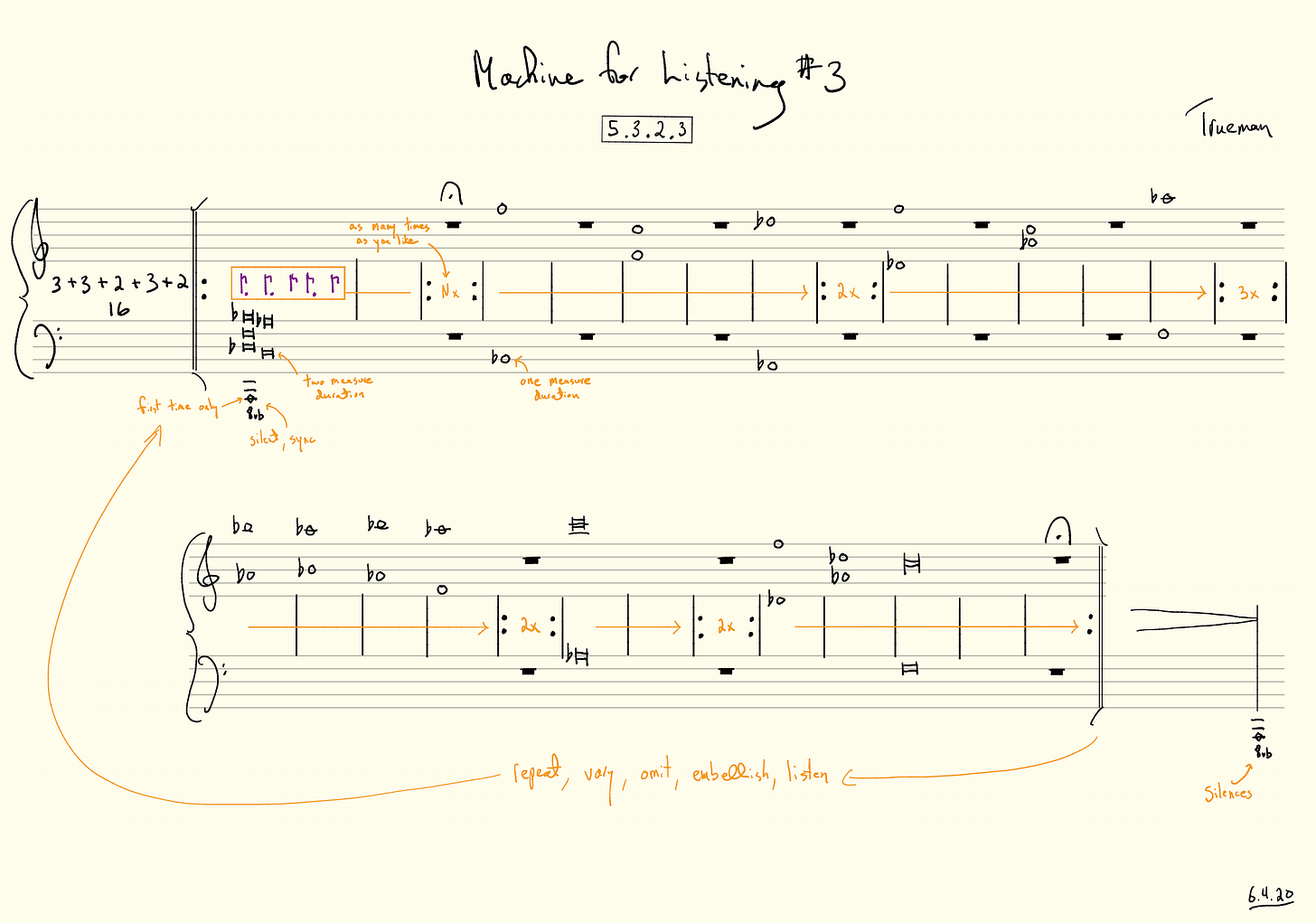

Like many interesting machines, the machine at the heart of all of the songs on The Seventeenth Hotel is simple in principle (unlike AI, for instance), yet yields complex, hard to anticipate (though always deterministic) results. The “blendrónic” preparation is a delay-based instrument with delay lengths that are reset rhythmically. The musician turns the virtual knobs (or sliders in this case), setting the rhythm of the changes (the “beat lengths”) and the “delay lengths” (which may be the same or different to one another) and off it goes, chopping up whatever it is fed (by playing notes on the keyboard):

The beat lengths (5:3:2:3 here, all multiples of a given pulse length set by a metronome in bitKlavier) determine when the delay lengths (also 5:3:2:3 in this case, again multiples of the same given metronomic pulse) change. These 5:3:2:3 values are the particular settings for Machine for Listening #3, one of the two machines used in “Giants Begone.”

Two additional parameters complete the controls for this machine. When the delay length changes, it can happen instantaneously (often yielding a click) or over a period of time (usually yielding some kind of chirp or swoop): the “smoothing” parameter, which itself can change every beat. Finally, the output of the machine can be fed back into itself, multiplied by some coefficient (less than 1 if you want to play it safely, but danger can also be interesting): the “feedback coefficients” parameter, which also can change every beat. Systems with feedback are often unstable and unpredictable, even if they are deterministic (chaos theory’s logistic equation is a classic case), and indeed that is the same here—the behavior of blendrónic is at its richest with feedback.

Playing a few notes to feed the machine, and then twiddling with these knobs while listening to what came out, is what led to the Machines for Listening. In machine #3, the sequence of beat and delay lengths are the same as one another—5:3:2:3 multiples of the given metronomic pulse-length (as in the video clip above)—and it yields a somewhat unstable feeling 3+3+2+3+2 beat pattern (notated in purple):

A fascinating aspect of machines like these is that changing a single parameter by a small value can lead to significantly different outcomes. For instance, the difference between machine #3 and #2 is only in the first parameter of the beat and delay lengths, changing them both from 5 to 4—one click of the knob:

This yields a very different rhythmic pattern, one that can be felt in 4 or 3 (see the purple rhythm notation below, and the subsequent audio example where I alternate between the two different feels):

I was literally just playing with these knobs, trying different values without thinking about it much—just listening and interacting intuitively with the machine—when the rhythmic patterns for machines #2 and #3 popped out.

Of course, the 4:3:2:3 pattern will be familiar to many, similar to the Yoruba bell pattern from West Africa or the pattern from Steve Reich’s Clapping Music (learn more!). The things you can find by playing with fun machines! In some ways, this relationship between the rigid calculus of a machine like blendrónic and the play it inspires is reminiscent of the “quantitative” and “qualitative” orientations towards African rhythm described in Kofi Agawu’s paper ‘Structural Analysis or Cultural Analysis? Competing Perspectives on the “Standard Pattern” of West African Rhythm.’ The paper has a particularly inspiring section later on describing a hypothetical kind of iterative composition process that includes “invoking cultural notions of playing, maneuvering, and teasing” with a basic embodied beat, yielding a wide and rich range of bell patterns. Curiously, Reich’s Clapping Music itself is much less about the African source of its central pattern than the machine-like process that the pattern is put through, a kind of centrifuge where systematic and inevitable rotations of the pattern against itself yield new composite patterns for us to revel in (or try to stay centered in, if we are playing the piece ourselves).

Attempting to stay centered is also a feeling we often have when playing with the blendrónic machine; we might feel a meter emerging from the machine one way, and then engage with it in that feel, only to discover that the machine then transforms the meter into something else, something that throws us off. The opposite can also happen, where we intentional try to sabotage the machine with a subversive, oddly placed note, only to hear it gradually reduce our input to something well behaved, converging on a pattern that becomes familiar (the previous audio clip seems to have qualities of both, converging on two different ways of feeling the meter, depending on how we play with it, and how we try to hear it).

In any case, both of these blendrónic machines (#2 and #3) are at work in “Giants Begone,” the 5:3:2:3 pattern for the bulk of it, and the 4:3:2:3 during the “choruses.” The transformation of feel from the 5:3:2:3 to the 4:3:2:3 and back was a particularly fun thing to explore compositionally, and is for me a key characteristic of the song.

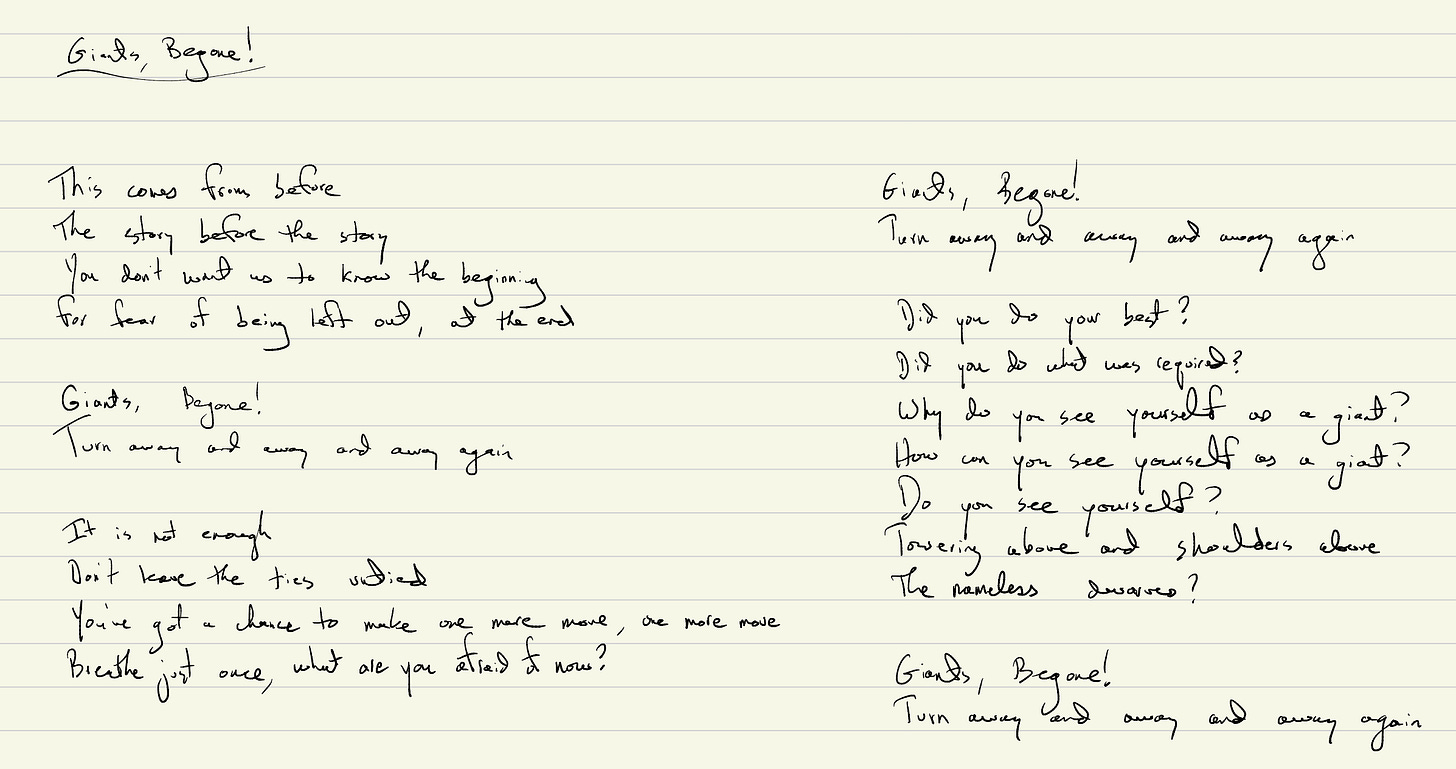

And now the words, about which I will say nothing, other than they have nothing to do with machines! Well, I will say this: I would like to acknowledge three particular people who have been very influential on me for many many years. From all of them I learned about designing things that are engaging to be musical with, usually through code, and have always found their music and work singular. Paul Lansky’s Things She Carried remains for me a remarkable example of what can happen when you build things and make music with them over the course of many many years. Brad Garton’s Rough Raga Riffs (listen) remains a touchstone for a how hand-made AI tools (made decades before the current hype!) can be part of a rich creative practice. And then there is Perry Cook, whose legendary paper “Principles for Designing Computer Music Controllers” is filled with pithy bits of wisdom that remain relevant today, including one of my favorite—“smart instruments are often not smart.” Indeed, bitKlavier is not smart at all, which is the way I like it—making music is already confusing enough…