The Seventeenth Hotel: Spare Me

the first track from a new album of songs

I am pleased to share the first track of a new album set to release later this year. Featuring the voice of my daughter Molly Trueman (check out her EP!), the album—The Seventeenth Hotel—is a product of quarantine collaboration—with Molly, as well as Jason Treuting, Matt Poirier, and Florent Ghys—followed by some years of revision and post-production. The first of the five tracks is the song “Spare Me:”

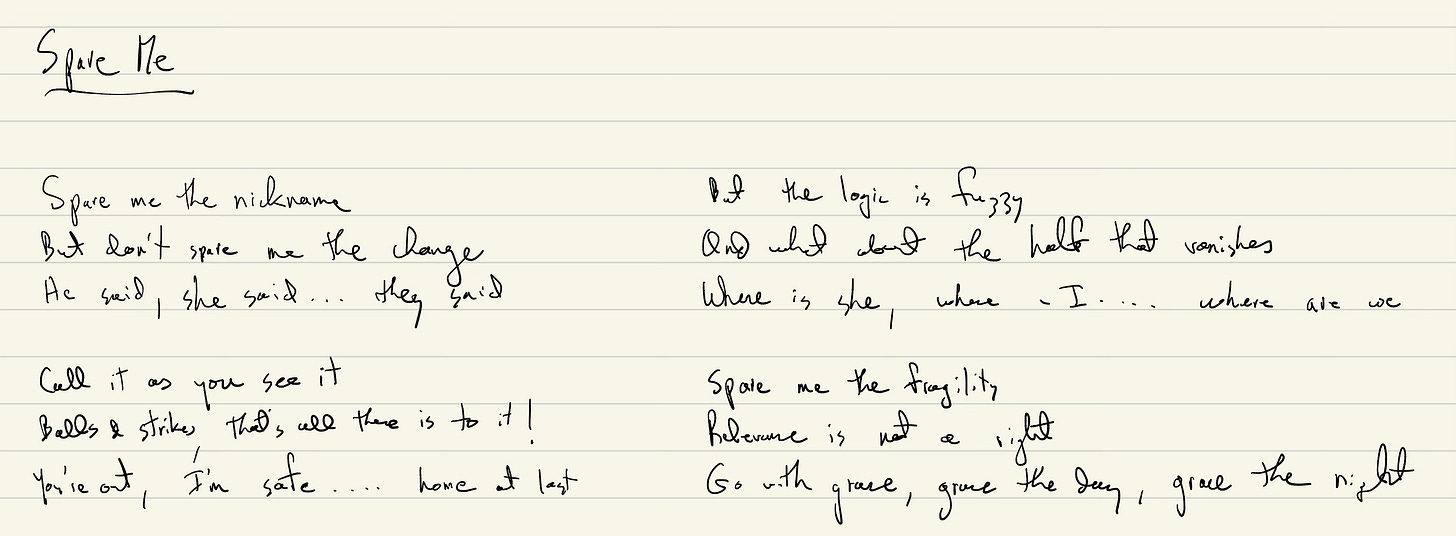

Spare Me

by Dan Trueman, track 1 from the album The Seventeenth Hotel, with

- Molly Trueman (voice)

- Jason Treuting (drums)

- Dan Trueman (bitKlavier and Hardanger d’Amore)

- Recorded by Molly Trueman, Dan Trueman, and Matt Poirier

- Mixed by Matt Poirier and Dan Trueman, Mastered by Matt Poirier.

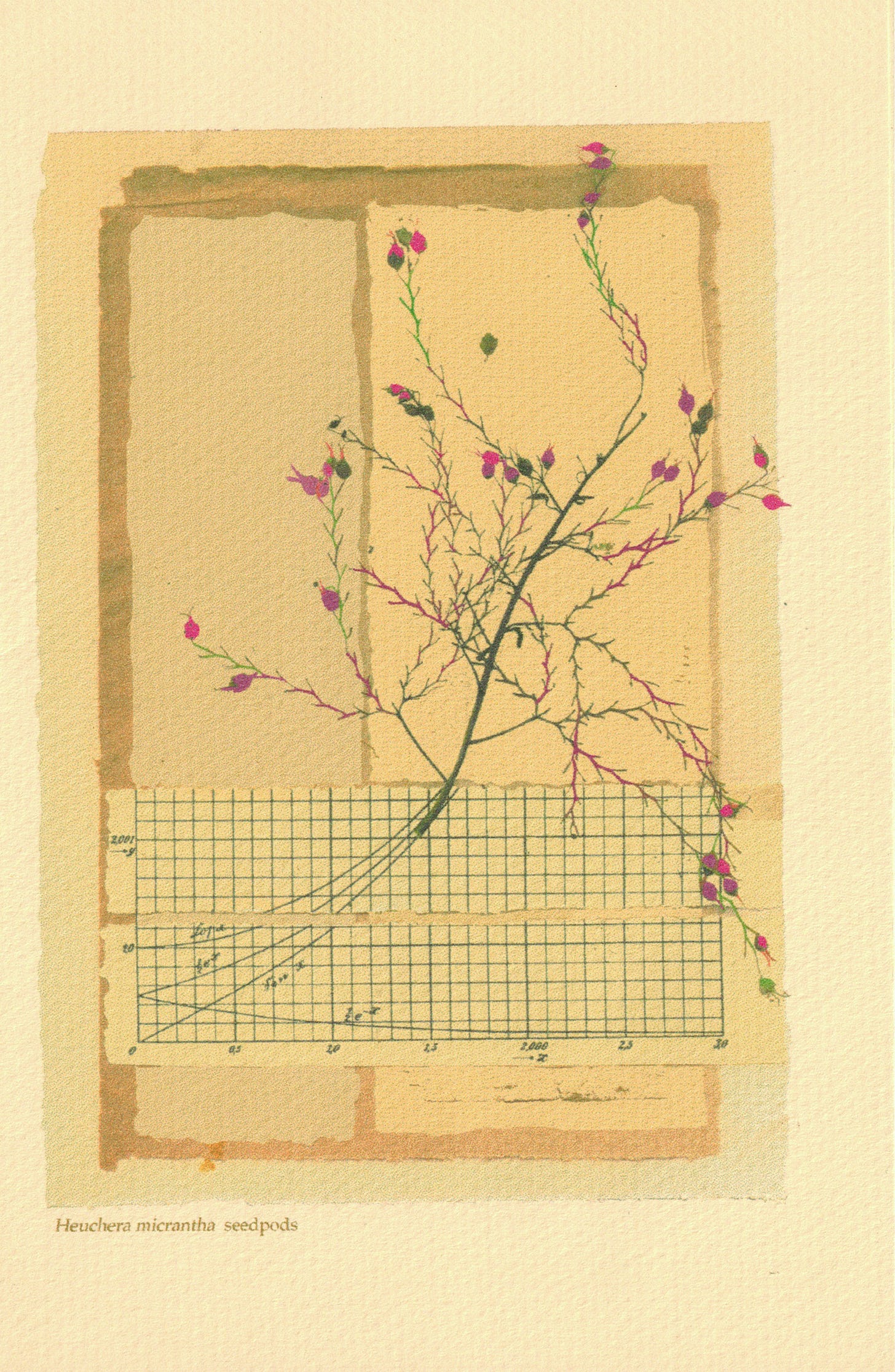

- Artwork by Judy Trueman

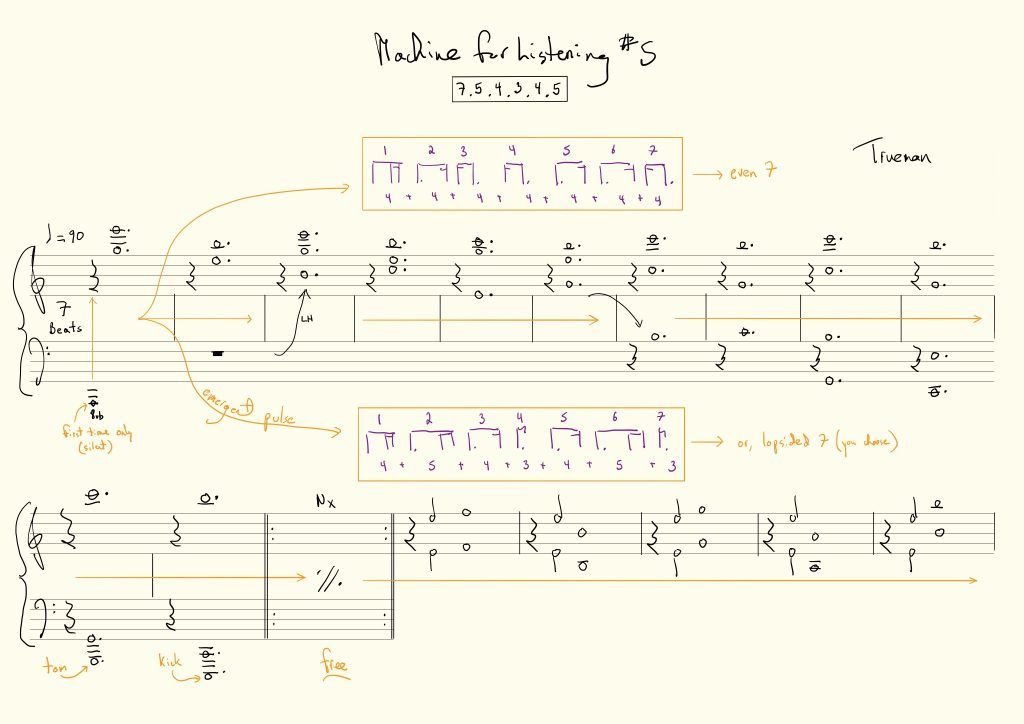

All of the songs on The Seventeenth Hotel emerged from explorations of a set of open form pieces I began in 2020, called Machines for Listening. From the notes for those:

Machine Listening is an important and complex field, focusing on teaching machines to listen and parse sound. But what about machines for listening, things that invite us to listen, teach us to listen?

These nine sketches are intended as active listening guides for bitKlavier, a kind of digital musical machine configured in specific ways to process the operator’s input and generate sound. Each “listening machine” has specific settings and interconnections that yield sometimes unexpected rhythms and textures, but are in fact completely deterministic — anything that seems like randomness is a product of the specific interactions between operator and machine. These are “open form” sketches, providing seeds, specific materials, and intentions for the operator to work with, strictly or loosely. They can be open ended, used at home as listening meditations, or can be the starting points for collaborations with other listeners and instrumentalists, perhaps through collaborative recording, or even live performance.

The Machines for Listening were sketched during June of 2020, with the world in imperfect lockdown and raging against centuries of racial injustice: silence is not an option, but listening is required. I’m indebted of course to the legacy of Pauline Oliveros, whom I had the pleasure of playing with many times years ago, and whose “machines for listening” are monumental. The cover (see below) is from a piece by my mother, Judy Trueman, that she used for her holiday card in the year 2000, a month after my daughter was born in Kingston NJ; in it she wrote “Happy Holidays to you two, the Princess of Kingston, the World, and the Universe.” We are in this together, after all.

The cover to Machines for Listening became the centerpiece for The Seventeenth Hotel album artwork:

My mother (Judy Trueman) passed away just as I was about to release this post. I’ll have more to say about that in the future, but for now I will just say that her artwork has graced many of my albums over the years, and indeed is all over the walls of my home. The image of dried, colorful flowers emerging from a grid of plotted equations matches perfectly the Machines for Listening, where unusual musical grids are the foundation for nonlinear growth, including the unexpected songs of The Seventeenth Hotel.

“Spare Me” emerged specifically from Machine for Listening #5, with this first page:

The “score” to all of the machines is here, and the galleries to explore them are built in to bitKlavier if you’d like to give them a try.

About those grids…

I made the Machines for Listening a few months after my father, Larry Trueman (1935–2019), a theoretical physicist, passed away. I studied physics as an undergraduate myself, and while that was long ago, those studies continue to be important to me in many ways. In addition to being a rigorous grounding in ways of knowing (or trying to know) the world, my education in physics had moments of what I can only describe as aesthetic experiences, the kind we expect from music. One in particular came in a culminating class on Maxwell’s Equations, taught by the wonderful Joel Weisberg, where I remember finally grasping the beautiful elegance of these four equations, but also being struck by their unavoidable asymmetries: like a stray elbow sticking out, these asymmetries defy tidy formulation and understanding of the laws of electromagnetism. For me, this realization, where the asymmetry both undermined and highlighted the otherwise beautiful symmetry of the equations, is what (if I remember correctly) triggered the aesthetic experience, and to this day makes me skeptical of neat and tidy explanations, or explanations that seem too comprehensive, too sure of themselves; I’m always looking for the stray elbow.

My father’s passing reminded me of these experiences, and also of a fascinating book I read back when I was a student called Inventing Reality: Physics as Language, by Bruce Gregory. I’ll quote two excerpts here:

Three umpires were discussing their roles in the game of baseball. The first umpire asserted, “I calls 'em the way I sees 'em.” The next umpire, with even more confidence, and a more metaphysical turn of mind, said, “I calls 'em the way the are!” But the third umpire, displaying a familiarity with twentieth-century physics, concluded the discussion with, “They ain't nothin' until I calls 'em!” The ball, the bat, and the plate do not create the game; the rules create the game, and the umpire interprets the rules, and in the process, creates the score. The players and the fans have no doubt that the ball was either over the plate or not over the plate, but the umpire's call, and not any fact of the matter, creates a ball or a strike. (p. 195)

And…

The word real…. seems to be an honorific term that we bestow on our most cherished beliefs—our most treasured ways of speaking…. The lesson we can draw from the history of physics is that as far as we are concerned, what is real is what we regularly talk about. For better or for worse, there is little evidence that we have any idea of what reality looks like from some absolute point of view. We only know what the world looks like from our point of view.

There are many older quotes that articulate various flavors of these ideas, like Werner Heisenberg: “What we observe is not nature in itself, but nature exposed to our method of questioning.” And, from Niels Bohr: “It is wrong to think that the task of physics is to find out how nature is. Physics concerns only what we can say about nature.” More from Bohr: “We are suspended in language in such a way that we cannot say what is up and what is down. The word 'reality' is also a word, a word we must learn to use correctly.”

And yet, the urge (at least among physicists) to find elegant explanations is fierce, and was a visceral attraction to me (still is, actually): another form of aesthetic experience I remember (and still sometimes get) is of delight, when I find a solution to a problem that I couldn’t see before. So there it is: my general state of mind, on a good day—delighted skepticism. Or would it be skeptical delight? Hmmm….

All this was not actually a digression! Rather, the embers of this line of thinking informed the lyrics for “Spare Me,” along with a wonderful New York Times article by the magnificent composer and thinker Marcos Balter, about the composer Joseph Boulogne, and a few other writings.

And that is as much as I will say about the lyrics…

p.s. a few years after reading the Gregory book, the study of so-called “fuzzy logic” was all the rage (in the wake of chaos theory, catastrophe theory, and so on; at least that’s how I remember it). I was enamored, and my father was deeply unimpressed; later, with vigorous irony, he got me a rice cooker that supposedly used some kind of fuzzy logic technology to determine whether the rice was done (they are still all over the place!). Dunno, it seems like maybe more of a marketing zing than reality, but what do I know. Well, I DO know this: some 25 years later, I still have that rice cooker, and it works great!

Congrats on this beautiful new release, Dan!!

OMG I completely have a fuzzy logic ricecooker too!!! Zojirushi + fuzzy Asian grammar logic for the win!!